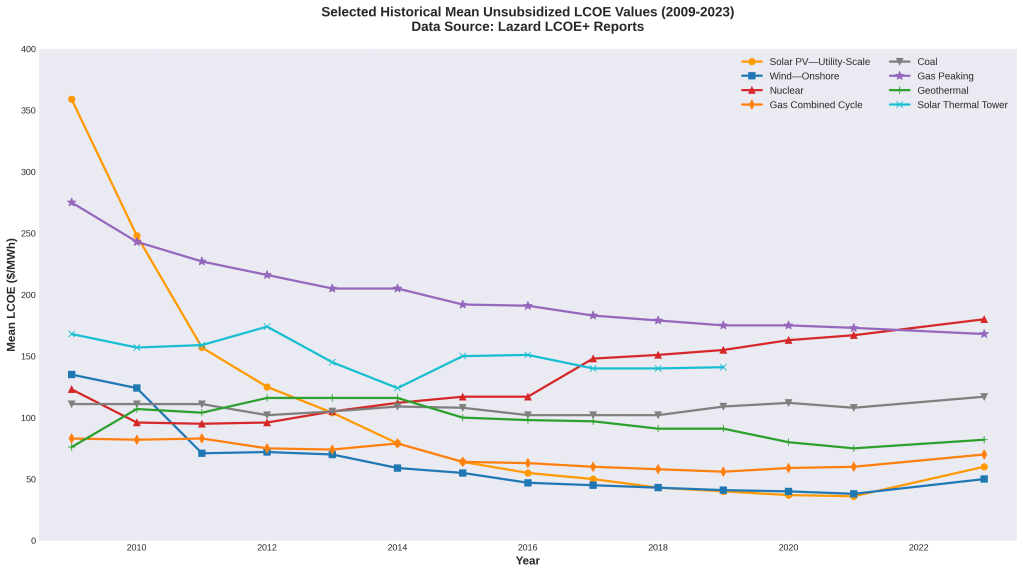

Over the past fifteen years, the cost of electricity generation has changed profoundly. In particular, solar and wind power have experienced dramatic reductions in their Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE). At the same time, public debate has remained stuck in oversimplifications: “solar and wind are the cheapest sources” or, conversely, “LCOE tells us nothing about real system costs.” Both statements contain elements of truth, but lack context. The key question for the coming decade is not whether LCOE will change further, but how, why, and what this implies for the electricity system as a whole.

What do the major LCOE studies predict?

The most frequently cited LCOE sources—Lazard LCOE+, Fraunhofer ISE, IEA/OECD, and the World Energy Outlook—present a remarkably consistent picture. Utility-scale solar PV and onshore wind are already among the lowest-cost options for new electricity generation and are expected to remain so through 2035. In nearly all scenarios, costs continue to decline, although at a slower pace than in the past.

Fraunhofer ISE estimates current LCOE values for Germany of approximately €0.04–0.07 per kWh for large-scale solar PV and €0.04–0.09 per kWh for onshore wind. In its outlook toward 2045, Fraunhofer expects further reductions, driven mainly by lower investment costs, higher full-load hours, and declining financing costs. The largest remaining cost reductions are no longer expected from panel prices themselves, but from system optimisation: improved integration, higher efficiency, and economies of scale.

Lazard’s LCOE+ (v16, April 2023) reaches similar conclusions for the United States. Utility-scale solar and onshore wind are now structurally cheaper than new gas-fired power plants, even without subsidies. The “plus” in LCOE+ explicitly accounts for storage and flexibility, showing that these add significant costs, but are themselves becoming cheaper over time.

Learning curves: why costs keep falling

Projected cost reductions over the next decade are not speculative. Both Fraunhofer and the IEA base their outlooks on empirical learning curves, which describe how costs decline as cumulative installed capacity increases. Historically, solar PV has exhibited learning rates of around 20–25% per doubling of capacity, while wind power shows learning rates of roughly 10–15%. For nuclear power and coal, comparable effects are largely absent.

This does not mean that solar costs will approach zero. The easiest and most dramatic cost reductions have already occurred. What remains are incremental improvements: higher efficiencies, reduced material use, standardisation, and lower capital costs. Most studies therefore project a further reduction of around 20–30% by 2035, rather than another order-of-magnitude decline.

Gas, coal, and nuclear: stagnation or rising LCOE

The outlook for conventional generation technologies is fundamentally different. New coal and gas plants face rising CO₂ prices, higher financing costs, and uncertainty about future utilisation. Fraunhofer shows that the LCOE of new gas-fired power plants may increase toward 2035, largely because these plants will operate fewer hours in systems with high shares of variable renewables.

Nuclear power occupies a distinct category. In theory, nuclear plants benefit from low fuel costs and long lifetimes. In practice, however, high upfront investment costs, long construction times, and financial risks dominate. Both Fraunhofer and the OECD demonstrate that the cost range for nuclear remains extremely wide and highly sensitive to assumptions about interest rates, construction schedules, and capacity factors. In most European scenarios, the LCOE of new nuclear does not decline structurally over the next decade, while renewable options continue to become cheaper.

Batteries and LCOE+: cheap generation becomes more expensive

One of the most important recent developments in LCOE analysis is the shift from “pure” LCOE to LCOE+, which explicitly includes storage, grid connection, and flexibility requirements. Lazard shows that battery costs are falling rapidly, but electricity supplied with storage remains significantly more expensive than electricity generated without it.

Most studies project that battery storage costs will decline by roughly 60–80% over the next decade. Even so, storage will continue to add several eurocents per kWh to electricity costs. As a result, the debate is shifting from “is solar cheap?” to “how much does reliable electricity cost?”—a much more relevant question.

Table: indicative LCOE development toward 2035 (new capacity)

| Technology | LCOE 2024 (€/kWh) | Expected 2035 (€/kWh) |

|---|---|---|

| Utility-scale solar PV | 0.04 – 0.07 | 0.03 – 0.05 |

| Onshore wind | 0.04 – 0.09 | 0.04 – 0.08 |

| Offshore wind | 0.06 – 0.11 | 0.05 – 0.10 |

| Gas CCGT | 0.10 – 0.18 | 0.14 – 0.25 |

| Nuclear (new build) | 0.14 – 0.49 | broadly similar |

| Solar PV + battery | 0.06 – 0.22 | 0.05 – 0.16 |

(Sources: Fraunhofer ISE 2024; Lazard LCOE+ 2023; OECD/IEA)

Implications for policy and public debate

Over the next decade, electricity from solar and wind will continue to become cheaper—but not free. The main cost challenge is shifting away from generation itself toward system integration: grid reinforcement, storage, flexibility, and dispatchable capacity. Focusing exclusively on headline LCOE figures underestimates these costs. Dismissing LCOE altogether, however, ignores the fact that investors and project developers use it daily to make real-world decisions.

The major studies converge on a clear conclusion: renewable electricity remains the lowest-cost option for new capacity, but a reliable electricity system requires additional investment. This moves the debate away from ideology and toward engineering and economics—where it belongs.

Conclusion

The outlook for the coming decade is clear: the LCOE of solar and wind continues to decline, fossil-based generation becomes more expensive or stagnates, and storage costs fall but remain significant. An honest discussion about electricity costs requires distinguishing between generation costs, system costs, and reliability. LCOE remains a useful metric, provided it is treated not as a final answer, but as a starting point for deeper analysis.

Leave a comment